Buried for millennia in the rear of a rock-shelter in the Lapedo Valley 85 miles north of Lisbon, Portugal, archaeologists uncovered the bones of a four-year-old child, comprising the first complete Palaeolithic skeleton ever dug in Iberia. But the significance of the discovery was far greater than this because analysis of the bones revealed that the child had the chin and lower arms of a human, but the jaw and build of a Neanderthal, suggesting that he was a hybrid, the result of interbreeding between the two species.

The finding casts doubt on the accepted theory that Neanderthals disappeared from existence approximately 30,000 years ago and were replaced by Cro-Magnons, the first early modern humans. Rather, it suggests that Neanderthals interbred with modern humans and became part of our family, a fact that would have dramatic implications for evolutionary theorists around the world.

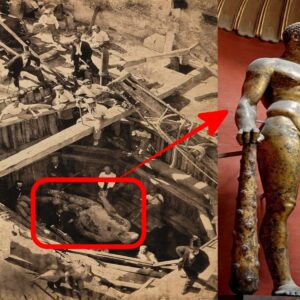

The discovery was made in November 1998 when archaeologists João Maurício and Pedro Souto went to the Lapedo Valley to investigate reports that prehistoric rock paintings had been found, which turned out to be true. In the course of their investigations they discovered a limestone rock shelter, the Lagar Velho site. The upper two or three meters of its fill had been bulldozed away in 1992 by the land owner, which left a hanging remnant of sediment in a fissure along the back wall, but this contained such a density of Upper Paleolithic stone tools, animal bones and charcoal that it was clear that Lagar Velho had been an important occupation site. Subsequent excavations confirmed this, producing radiocarbon dates of 23,170 to 20,220 years age.

While collecting surface material that had fallen from the remnant, João and Pedro inspected a recess in the back wall. In the loose sediments they recovered several small bones stained with red ochre they thought could be human. This turned out to be a child’s grave, the only Paleolithic burial ever found in the Iberian Peninsula.

This child had been carefully buried in an extended position in a shallow pit so that the head and feet were higher than the hips. The body had been placed on a burned Scots pine branch, probably in a hide covered in red ochre. The ochre was particularly thick around the head and stained the upper and lower surfaces of the bones. A complete rabbit carcᴀss was found between the child’s legs and six ornaments were found – four deer teeth which appear to have been part of a headdress, and two periwinkle shells from the Atlantic, which are thought to have been part of a pendant.

An excavation project was launched to retrieve all the remnants of the child’s body. The work was difficult because tiny plant roots had penetrated the spongy bones. Sieving of the disturbed sediments led to the recovery of 160 cranial fragments, which consтιтute about 80 percent of the total skull. The bulldozer had crushed the skull but fortunately had missed the rest of the body by two centimetres.

Once the recovery process was complete, the skeletal remains were sent to anthropologist Erik Trinkaus from Washington University to analyse the remains. This is when the most surprising discovery was made. Trinkaus found that the proportion of the lower limbs were not those of a modern human but rather resembled those of a Neanderthal. On the other hand, the overall shape of the skull is modern, as is the shape of its inner ear, and the characteristics of the teeth. Although the skull was most similar to that of a modern human, one anomaly was detected – a pitting in the occipital region which is a diagnostic and genetic trait of Neanderthals.

Trinkaus concluded that the Lapedo child was a morphological mosaic, a hybrid of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans. Yet the two human forms are not thought to have coexisted later than 28,000 years ago in Iberia. How could the child have features of both forms? The question led to a bitter debate among experts, some of whom accepted that the discovery of the Lapedo child proved that Neanderthals interbred with modern humans, while others refused to part with long-held views that the Neanderthals died out and were replaced by another species.

Today, the most popular theory is that the remains are that of a modern child with genetically inherited Neanderthal traits – which means that the last Neanderthals of Iberia (and doubtless other parts of Europe) contributed to the gene pool of subsequent populations.