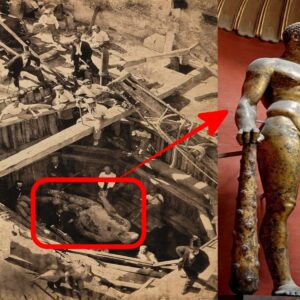

While dredging a flooded quarry for gravel, workers in Kent, England, stumbled upon the remains of a ship dating back to the 16th century.

Unsure of what they’d unearthed, they turned the investigation over to experts from Wessex Archaeology. Though the quarry is located about 1,000 feet from the coast, archaeologists suspect the site was once on the coastline.

Few ships from the Elizabethan era have survived, so the find could provide important insights into a “great period of change in ship construction and seafaring,” says Andrea Hamel, a marine archaeologist with Wessex Archaeology, in a statement announcing the discovery.

With funding and support from Historic England, a government body that helps protect the country’s heritage, archaeologists studied 100 timbers from the ship. By looking at the timbers’ tree ring growth patterns, a process known as dendrochronological analysis, they determined that shipbuilders constructed the vessel from English oak trees that grew between 1558 and 1580.

That timeline makes sense given how the ship was constructed: Crews built the internal framing first, then later added flush-laid planking to build the outer hull. Shipbuilders used this technique to assemble the vessels that would “explore and settle along the Atlantic coastlines of the New World,” per the statement.

At the time of the ship’s construction, northern European shipbuilders were transitioning to this style. Before that, shipbuilders primarily used traditional clinker construction methods, popular among the Vikings, which featured overlapping planks.

The ship sailed during a time when trade was expanding, and the English Channel served as a bustling thoroughfare for commercial vessels, say the researchers. “Although the ship remains unidentified,” they adds, “it represents an era when English vessels and ports played an important role in this busy traffic.”

They suspect that the vessel was abandoned when its condition deteriorated, or that it wrecked on the coast.

“The remains of this ship are really significant, helping us to understand not only the vessel itself but the wider landscape of shipbuilding and trade in this dynamic period,” says Antony Firth, who leads marine heritage strategy for Historic England, in the statement.

The vessel’s chances of surviving this long were slim: Wood that’s exposed to water and air typically only persists for a few years before rotting away, writes Live Science’s Tom Metcalfe. But in this case, a layer of silt may have protected the ship from oxygen.

Archaeologists also used digital photography and laser scanning technologies to study the ship. Once they finish their analysis, they plan to rebury the vessel’s timbers to protect them for years to come.