During the early twentieth century, Howard Carter, a British Egyptologist, excavated for many years in the Valley of the Kings—a royal burial ground located on the west bank of the ancient city of Thebes, Egypt.

When Carter arrived in Egypt in 1891, he became convinced there was at least one undiscovered tomb–that of the little-known Tutankhamen, or King Tut, who lived around 1400 B.C. and died when he was still a teenager.

Backed by a rich Brit, Lord Carnarvon, Carter searched for five years without success. In early 1922, Lord Carnarvon wanted to call off the search, but Carter convinced him to hold on one more year.

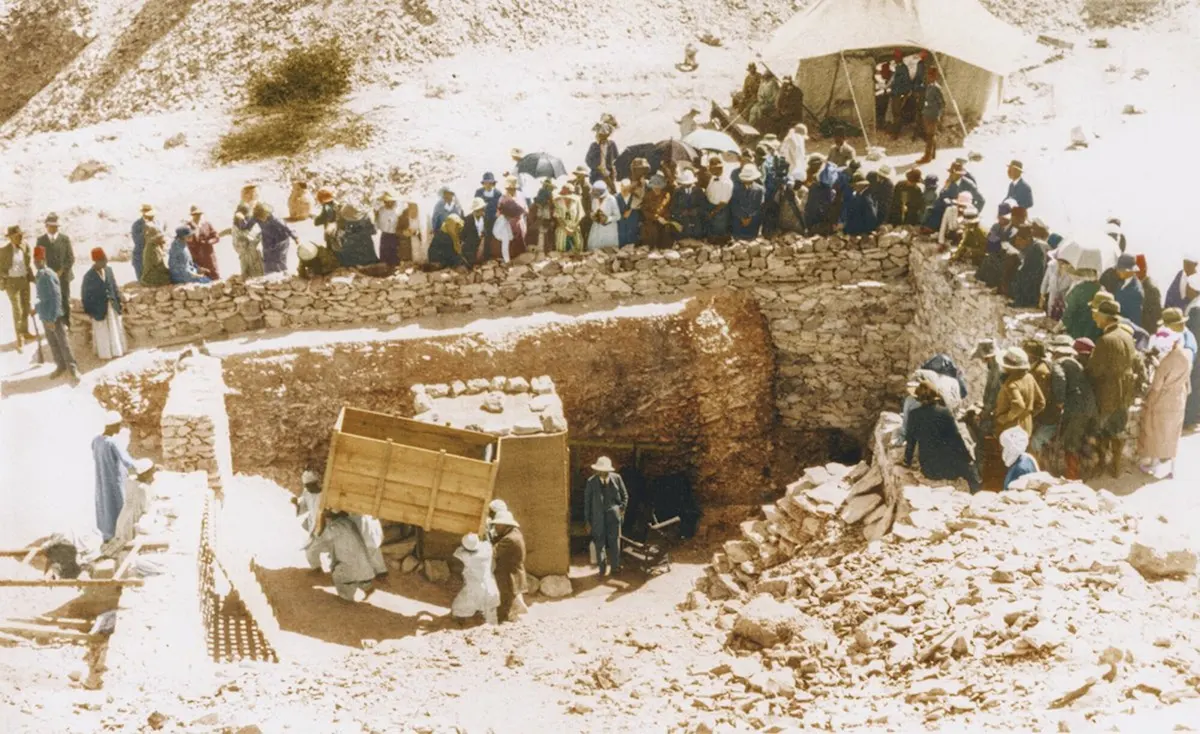

Finally, the wait paid off when Carter came upon the first of twelve steps of the entrance that led to the tomb of Tutankhamun. He quickly recovered the steps and sent a telegram to Carnarvon in England so they could open the tomb together.

Carnarvon departed for Egypt immediately and on November 26, 1922, they made a hole in the entrance of the antechamber in order to look in.

Howard Carter, Arthur Callender and an Egyptian worker open the doors of the innermost shrine and get their first look at Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus.

Carter recalled: “At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the lights, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold –everywhere the glint of gold”.

When Carter and Lord Carnarvon entered the tomb’s interior chambers on November 26, they were thrilled to find it virtually intact, with its treasures untouched after more than 3,000 years.

The men began exploring the four rooms of the tomb, and on February 16, 1923, under the watchful eyes of a number of important officials, Carter opened the door to the last chamber.

Inside lay a sarcophagus with three coffins nested inside one another. The last coffin, made of solid gold, contained the mummified body of King Tut.

Among the riches found in the tomb–golden shrines, jewelry, statues, a chariot, weapons, clothing–the perfectly preserved mummy was the most valuable, as it was the first one ever to be discovered.

A ceremonial bed in the shape of the Celestial Cow, surrounded by provisions and other objects in the antechamber of the tomb.

Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus held not one but three coffins in which to hold the body of the king. The outer two coffins were crafted in wood and covered in gold along with many semiprecious stones, such as lapis lazuli and turquoise. The inner coffin, however, was made of solid gold.

When Howard Carter first came upon this coffin, it was not the shiny golden image we see in the Egyptian museum today. In his excavation notes, Carter states, it was “covered with a thick black pitch-like layer which extended from the hands down to the ankles.

This was obviously an anointing liquid which had been poured over the coffin during the burial ceremony and in great quantity (some two buckets full)”.

A gilded lion bed, clothes chest, and other objects in the antechamber. The wall of the burial chamber is guarded by statues.

The tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, it seems clear that these robberies took place within several months at most of the initial burial.

Eventually, the location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by stone chips from subsequent tombs, either dumped there or washed there by floods. In the years that followed, some huts for workers were built over the tomb entrance, clearly without anyone’s knowing what lay beneath.

When at the end of the 20th Dynasty the Valley of the Kings burial sites were systematically dismantled, Tutankhamun’s tomb was overlooked, presumably because knowledge of it had been lost, and his name may have been forgotten.

An assortment of model boats in the treasury of the tomb.

In total 5,398 items were found in the tomb, including a solid gold coffin, face mask, thrones, archery bows, trumpets, a lotus chalice, food, wine, sandals, and fresh linen underwear. Howard Carter took 10 years to catalog the items.

Recent analysis suggests a dagger recovered from the tomb had an iron blade made from a meteorite; study of artifacts of the time including other artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb could provide valuable insights into metalworking technologies around the Mediterranean at the time.

For many years, rumors of a “Curse of the Pharaohs” (probably fueled by newspapers seeking sales at the time of the discovery) persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had entered the tomb.

A study showed that of the 58 people who were present when the tomb and sarcophagus were opened, only eight died within a dozen years.

All the others were still alive, including Howard Carter, who died of lymphoma in 1939 at the age of 64. The last survivor, American archaeologist J.O. Kinnaman, died in 1961, a full 39 years after the event.

A gilded lion bed and inlaid clothes chest among other objects in the antechamber.

Under the lion bed in the antechamber are several boxes and chests, and an ebony and ivory chair which Tutankhamun used as a child.

A gilded bust of the Celestial Cow Mehet-Weret and chests sit in the treasury of the tomb.

Chests inside the treasury.

Ornately carved alabaster vases in the antechamber.

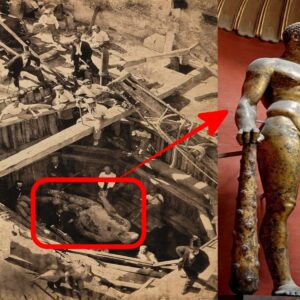

In a “laboratory” set up in the tomb of Sethos II, conservators Arthur Mace and Alfred Lucas clean one of the sentinel statues from the antechamber.

Howard Carter, Arthur Callender and an Egyptian worker wrap one of the sentinel statues for transport.

Arthur Mace and Alfred Lucas work on a golden chariot from Tutankhamun’s tomb outside the “laboratory” in the tomb of Sethos II.

A statue of Anubis on a shrine with pallbearers’ poles in the treasury of the tomb.

Carter, Callende, and two workers remove the partition wall between the antechamber and the burial chamber.

Inside the outermost shrine in the burial chamber, a huge linen pall with gold rosettes, reminiscent of the night sky, covers the smaller shrines within.

Carter, Callender and two Egyptian workers carefully dismantle one of the golden shrines within the burial chamber.

Carter examines Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus.

Carter and a worker examine the solid gold innermost sarcophagus.

Lord Carnarvon, financier of the excavation, reads on the veranda of Carter’s house near the Valley of the Kings.

Tutankhamun’s Tomb: The gold mask in situ on the mummy of the King, still inside the third (innermost) solid gold coffin.

Howard Carter (left), Arthur Mace and an Egyptian workman standing on scaffolding, roll back the linen pall which lay over a gilded, wooden frame between the first (outermost) and second shrines.

One of only two images showing Howard Carter (on the left) and Lord Carnarvon together in the tomb; they stand in the partially dismantled doorway between the Antechamber and the Burial Chamber. Lord Carnarvon died less than two months after this photograph was taken.

Tourists crowd around the entrance to the tomb to watch a large object, possibly a couch from the Antechamber, being removed from Tutankhamun’s tomb, on its way to the workroom.

Howard Carter accompanies the wooden portrait figure of Tutankhamun (the so-called mannequin of uncertain purpose) on its way to the workroom (tomb KV 15, of Sethos II). Sitting on the wall on the left is Lord Carnarvon; behind him walks Arthur Weigall, a former Antiquities Service Inspector.

At Thebes, Howard Carter escorts an ornamental gilt and inlaid casket to the workroom. Carter thought the contents of this box had been ‘gathered hastily together after the robbery was discovered and thrown carelessly into the box’. They included pieces of gold openwork, two adzes, a glove, a faience collar and a leopard skin robe.

Howard Carter (on the left) accompanies the body of one of Tutankhamun’s chariots to the workroom. Made of wood, with rawhide tyres, this chariot was highly decorated with gold, colored glass, and stone inlay, and probably used on ceremonial occasions.

Standing outside tomb KV 6, of Ramesses IX, are members of the archaeological team including Harry Burton (third from left) and Howard Carter (fourth from left).

From Tutankhamun’s tomb, Statuettes of Geb, Sakhmet, Kebehsenuf and Duamutef from inside black, wooden shrines found against the eastern wall of the Treasury.