Courtesy American Swedish Institute

Minnesota has the largest Scandinavian American population in the U.S., according to the Census Bureau. But if not for the American Swedish Institute, in south Minneapolis, the Twin Cities’ handle on Nordic culture might stop at lutefisk, “uff da,” and standoffishness. Think of the maypole-circling Midsommar, the crayfish-scarfing Kräftskiva (August 23), or last spring’s egg-shaped sauna—ASI demonstrations many degrees farther north.

This spring through fall, ASI now re-introduces Minnesotans to the Vikings, in one of the biggest exhibits yet at the Scandinavian culture and history museum. The ancient Nordic seafarers did more than plunder, defile, and binge-drink their way to NFL poster-boy status, as new research shows.

The Vikings Begin, on display until October 27, rolls out about 40 artifacts dating some 1,400 years back. Excavated from Swedish burial grounds, they span weapons, jewelry, helmets, and other riches, predating the Norse warriors’ biggest raids by a few centuries. Overseas for the first time, they now fill ASI’s Osher Gallery and Turnblad Mansion. Minneapolis makes the third and final stop on a two-year U.S. tour, following stints in Connecticut and Seattle.

ASI dims the lights, circulates epic music, projects videos of smudy-eyed actors (with research suggesting that Vikings did wear eyeliner).

And the effect is disorienting. Minnesotans have the football team, yes, but popular culture has long treated the Vikings as public-domain history. We’ve dressed them in the (debunked) horned helmets of Richard Wagner’s 19th-century operas; reduced them to the Sunday-comic barbarism of Hägar the Horrible; and adapted what we know of their spirituality for the Marvel Comics universe—while clumsily bundling them with the byword “rape and pillage.”

Despite or because of that ubiquity, the exhibit, on loan from Gustavianum, the Uppsala University Museum in Sweden, makes the Vikings feel real for the first time.

“The main misconception, very much enhanced by the TV series and other depictions, is that brutality and cruelness were their basic characteristics,” says Gustavianum director Mikael Ahlund. (The History Channel’s Netflix-bingeable Vikings prides itself on nailing details but also hypes medieval violence.) “This has prevented many people from seeing and understanding the sophistication of their society.”

Researchers have overlooked that sophistication, too, according to the three archaeologists who recently assessed the artifacts on display. The Vikings left no written history, no religious texts, no records of trade. We have burial-site finds, plus Old Norse runes, plus the biased accounts of Anglo-Saxons—wherein churchmen describe hellish raids on unprotected monasteries.

If academics have tried to fill in the gaps since about the ’70s, they left key work unfinished: Gustavianum’s assets, around since the ’20s, have escaped modern analysis until now.

“We have a new chance to [re-examine the exhibit’s materials], with DNA and other analytical methods,” says Gustavianum conservator and exhibit manager Emma Hock. “So it’s quite an exciting time for the University, as well.”

Who were—or, weren’t—the Vikes? Here’s what we found out.

Boat installation

Courtesy American Swedish Institute

Male, Maritime, and Violent

I. Male

Price breaks down the Viking stereotype into three parts: “male, maritime, and violent.”

And the Gustavianum team’s adjustments to that stereotype deal in subtleties, at least at first. Visitors enter ASI’s Osher Gallery, surrounded by wall-size images of stormy seas. In the center, a boat installation replicates the type pre-Vikings used in burial, where the artifacts on display would have turned up.

In addition to weapons and tools, the warrior might have gone under with horses, dogs, sheep, goats, pigs—enough to surround him, or, significantly, her, with a menagerie of skeletons, as seen in photographs in the Turnblad Mansion.

We know “or her” thanks to genomic data: In 2017, Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, another of the three Gustavianum archaeologists, reclassified the remains of an eminent Viking warrior, buried with weaponry and two horses, as biologically female—not male, as long thought.

“We often think of Vikings as men only. This is wrong,” Price says, “at least if you refer to Scandinavians in general. Women could be as far-travelled and battle-minded as men were.”

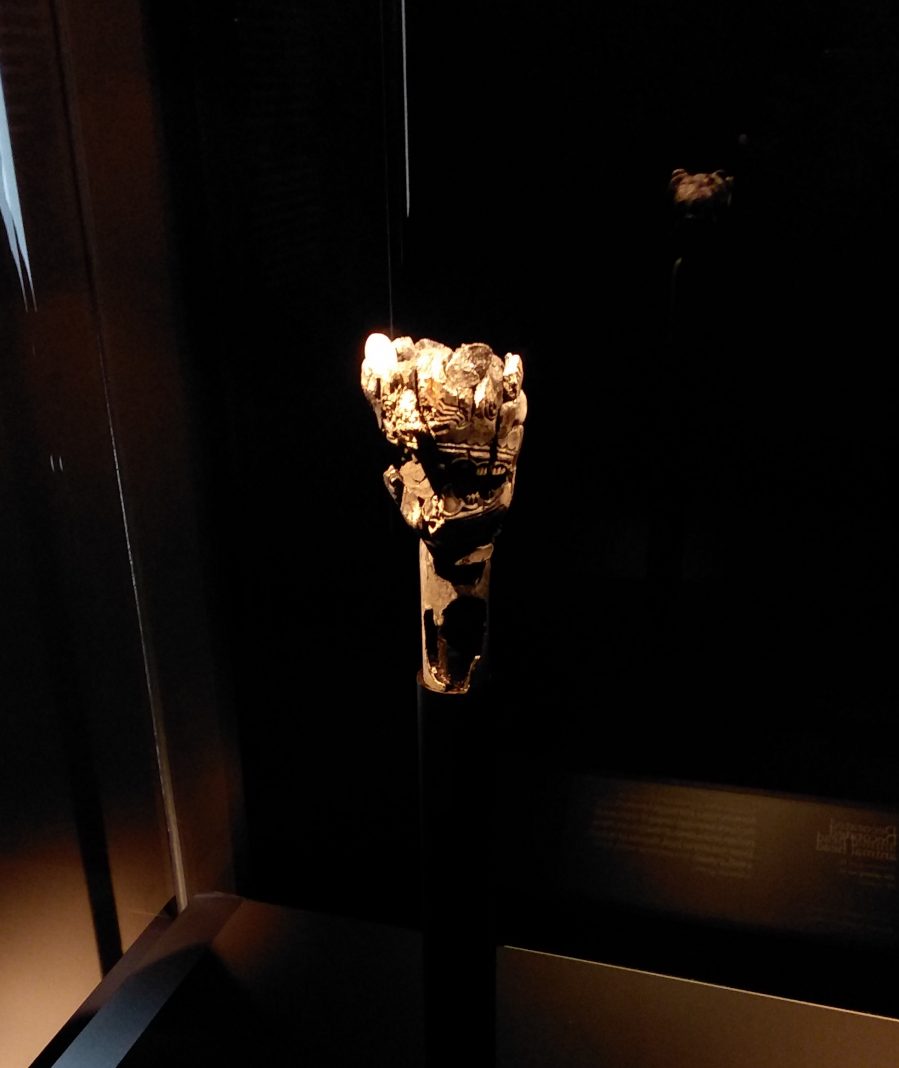

Animal-headed staff

Photo by Erik Tormoen

Women took control outside of fighting, too. “Whether as queen of the land or ruler of a household, women wielded power, especially in the absence of their mate,” Price notes.

Still, in male-dominated Viking society, most women would remain on the homestead. The genders were never fully equal, according to Price.

No Vikings Begin artifacts directly invoke those battle-minded among the women, but a peculiar aspect of their clout comes through a more ethereal channel: An animal-headed staff likely served a type of priestess, Price says. The Vikings appear to have considered women closer to the realm of spirits, with purview over death and the future.

“The Vikings Begin” takes visitors through the Osher Gallery and the Turnblad Mansion in south Minneapolis

Courtesy American Swedish Institute

II. Violent

When it comes to brutality, there’s less to correct. “We should not seek to emulate or admire these guys,” Price says. “The Vikings, or their Vendel [pre-Viking] predecessors, were not heroes at all.”

Coming by seas and waterways, raiders weaponized the element of surprise. Price describes Viking culture as “strong-arm,” one that ultimately “disintegrated in civil war, famine, and carnage.”

But why did they become as violent as they did? The answer is surprisingly relatable.

Scandinavian economies long relied on farming, hunting, and fishing. But then, around 550, two volcanoes exploded.

The eruptions tossed enough material into the atmosphere to block out the sun for over a year. Temperatures dropped. Agriculture shriveled. Suddenly, Scandinavians contended with a kind of climate change. Less relatably, historians believe this wiped out 50% of their population.

Around that time, Scandinavia got new neighbors, too. The Roman Empire collapsed, the Huns rampaged. Across the continent, trade routes reformed, technology advanced, and wealth spread. Raiding meant easy access to gold, slaves, and control of trade resources—not to mention new land for farming.

The Baltic region, east of Sweden, made good testing waters, where pre-Vikings refined voyaging and raiding techniques over several hundred years. By the Viking period (from the eighth to eleventh centuries, roughly), they had streamlined weaponry.

Sword

Photo by Mikael Wallerstedt/UPPSALA UNIVERSITET

But prior to that, weapons inspired profound craftsmanship, as seen in Vikings Begin. “Every time I look at all the work that went into a sword handle—or the leather sheathes, with embossed leather, with little seams—the intricacy involved, and the workmanship to produce such a decorated object that is then buried with the individual, is really quite remarkable,” Hock says.

Combat practice had worked its way into everyday life. A martial hierarchy made kings and queens of warriors. “Here were also organization, skills, and social structures to the violence,” writes Hedenstierna-Jonson, in a book accompanying the exhibit.

Viking shield

Viking shield

Photo by Erik Tormoen

On display, the handle of a massive sword glitters with minuscule rubies. A flotsam-chunk of hull bears fossilized grooves, imprinted by a bundle of arrows. A shield, too big for battle, likely sat, propped up, for show. Brass helmets hid faces behind curtains of chain mail—more sensible than Wagnerian horns.

Price, on the press tour, described engravings carved into the domes of some pre-Viking helmets. Glimmering when they caught the light, the pictographs would have appeared to move—”crawling” across the Viking’s scalp.

It makes sense that Vikings counted honor, glory, and loyalty among their ideals, according to runic research. Dependence on farming gave way, and aristocratic warriors flaunted their weapons and jewelry. Pre-Vikings built grave mounds over funeral pyres. They started burying their best in boats.

Italian glassware found in boat graves

Italian glassware found in boat graves

Courtesy American Swedish Institute

III. Maritime

Which brings us to the third cliché: “maritime.”

Here, consensus is strong: Ancient Scandinavians were excellent seafarers. Centuries before they became Vikings, they colonized the Baltic Islands and built boats of various designs. Sagas refer to “sunstones,” or sundials used in navigation.

A softer side surfaces in Viking foreign relations, too: While rough, they also dabbled in diplomacy and engaged in commerce.

“A much more exciting perspective is that trade, rather than violent raids, was the main driving force for their far-ranging travels,” says Ahlund. So far-ranging, pre-Vikings would encounter peoples from at least 52 contemporary cultures.

Viking jewelry, including amber beads (right)

Viking jewelry, including amber beads (right)

Courtesy American Swedish Institute

Vikings Begin offers evidence of these dealings: Apart from Scandinavian-made amber beads, an imported variety loops along a Nordic-metal necklace. Technicolor glass bowls hail from northern Italy. Arabic coins prove contact with the Middle East. Brass measuring scales, pocket-size for travel, would have assisted fair exchange during ventures that reached as far as the Silk Road.

Scales

Scales

Photo by Erik Tormoen

In new, pre-Viking hubs, immigrants arrived, cultures blended. “One can only imagine the polyglot of languages that could have been heard in the streets of a market town,” Price writes.

Regularly moving to and from distant lands, Price continues in the book, the pre-Vikings travelled “as pirates, mercenaries, and, later, effectively as soldiers on military campaigns; as politicians, diplomats, and envoys; as colonists, settlers, as people in search of a new life; and, yes, even as explorers, genuine adventurers journeying over an unknown horizon.”

Eventually, sailing expertise landed them in North America—the first known Europeans to get there. (They probably didn’t post up in now-Minnesota, as some claim—but more on that later.)

In the end, the Gustavianum team goes so far as to call the Vikings one of the most cosmopolitan, tolerant cultures of the European past.

“The Vikings Begin” at the American Swedish Institute runs through October 27

“The Vikings Begin” at the American Swedish Institute runs through October 27

Courtesy American Swedish Institute

The Raids Will Be Televised

After walking through Vikings Begin, it’s tempting to slink back home and turn on some of the Vikings programming that Ahlund warned against. We have a lot of it—a pagan invasion of streaming services.

Of note: the action-packed, shadowy TV drama The Last Kingdom; the farcical, The-Office-meets-the-History-Channel Norwegian comedy Norsemen; the docu-style, defensively titled educational romp Real Vikings.

And the History Channel’s own Vikings, on Netflix, enjoys popularity for the same reasons Game of Thrones did. There are epic soap-opera twists. Strong and compelling female characters. Transportive medieval theatrics. Cool fashions.

Vikings follows the myth of Ragnar Lodbrok, of Old Norse poetry. At ASI, video projections don’t look far off, visually, from the History Channel show. Bejeweled and braided, the Vikings were more “Johnny Depp than Vin Diesel,” as National Geographic recently put it.

Critics have fussed over the ways Vikings both flouts and flaunts factuality. Women warriors have precedent, as mentioned above. Also true to history, Vikings platters up violence. But because entertainment favors average viewers over academics, there’s some chafing going on. If we’ve corrected our understanding of one Viking warrior’s sex, for instance, that doesn’t mean we’ve grasped Viking views on gender. Socially active women, while interesting of Viking society, also add to a 2019 script.

“In general, I’m very reluctant to draw messages from the past for the present,” Price says, of pre-Viking research. “Even apparent positives—a relatively egalitarian perspective on the rights of women, for example—have often been exaggerated, and we need to beware of projecting our contemporary values onto a past that sadly did not always share them.”

Conflating the ancient and the modern, at worst, gets downright toxic. Certain white supremacists have demonstrated as much, claiming the Vikings for racist ends (with some observers loosely tying the phenomenon to Vikings‘ popularity).

In May 2017, a white supremacist posted “Hail Vinland!!! Hail Victory!!!” on Facebook days before killing two people in Portland, Oregon—”Vinland” referring to part of North America supposedly settled by Leif Erikson. In March, a white supremacist in New Zealand killed 50 Muslim men, women, and children. His bid for media attention, in a “manifesto,” referred to medieval religious wars and used the symbol of a black sun, Sonnenrad, linked to Old Nordic cultures.

Propagandist theft of the Sonnenrad goes back to German nationalism, when Nazi scholars, threatened by Germany’s waning power, traced an ascendant, white Germanic race to Viking expansion.

But expansion, Price would point out, isn’t the right word. That term “has connotations of deliberation and process.” Diaspora better captures the gradual, exploratory raiding, trading, and colonizing, with Vikings’ broad influence “the unintended result of numerous entangled movements and interactions … resulting in a variety of equally unforeseen longer-term legacies.”

Ironically, it was assimilation that helped the Vikings ride out their own epoch of international stress and flux, according to the Gustavianum team. They became multicultural, and Vikings Begin presents them as open and adaptive—the sort who would treasure foreign riches gained through trade; who would even bury their dead with them.